| |

|

|

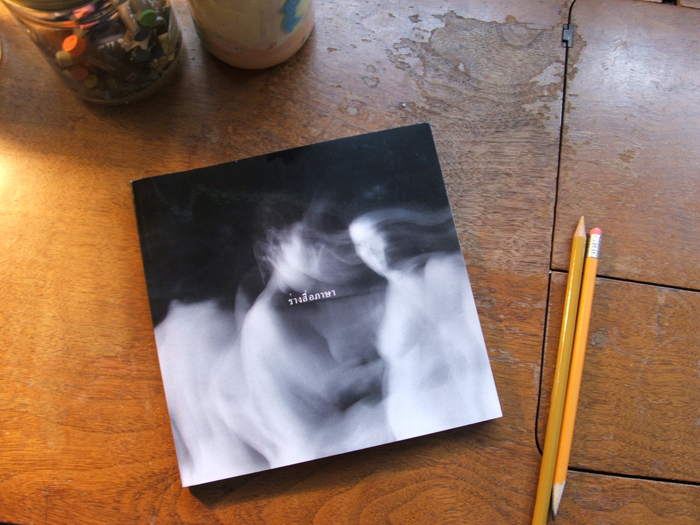

***First published in Language In-Form: Works by Wanrudee Buranakorn, Ed. Sean Ford, translated into Thai and printed in conjunction with the correlating exhibition at Seven Art Gallery, Bangkok, Thailand (2010). Reprinted here with permission.

The Artist and Her Muse

By Stacy Elaine Dacheux

Veils are ladylike.

Veils have sound tracks in the sense that they carry emotion or drama when lifted. They are personal and political, especially when forced upon an individual. Veils are theatrical scrims too, transitioning one scene into another, depending on the lighting cues, and what content demands masking or illumination.

“Veil,” a photographic series by Wanrudee Buranakorn, is not so much about the veil itself as it is about the power around it or the struggle to break free from it.

Each of Buranakorn’s black and white prints depicts the female figure pushing against a semi opaque white sheath, which extends beyond the length of her body. Each shot, ranging in composition and scope, indicates movement, or action bubbling up from below the surface.

The New Oxford American Dictionary defines “veil” as several types of concealments, the most interesting of which is “a membrane that is attached to the immature fruiting body.”

Buranakorn’s veil imagery works in a similar manner, as a casing that holds the developing figure of a woman. However, instead of protecting, the membrane traps. The figure, striving to escape, applies pressure, melding into its sheath. With an attempt to find movement, the body only finds more body.

This erotic tethering speaks to Auguste Rodin’s nude sculptures. For instance, his piece Torse d’ Adéle (1882) depicts the female bodice erupting from its maker’s block. This bodice is fragmented, pushed up in parts-- devoid of full arms, legs, and head, thus generating a sense of half-emergence, strapping the female body into being an object of desire. We are stunned, not only by its pristine craftsmanship, but also by the erotic energy and unfortunate containment of this energy. The bodice’s curves are remarkably lifelike, yet the woman is not a woman at all. Her mutilated identity is mostly physical and molded by her maker’s male viewpoint.

Buranakorn’s “Veil” series incorporates the same texture and entrapment of these old world sculptural masterpieces, such as Rodin’s, in order to engage, not imitate. As an artist, Buranakorn conveys the figure’s struggle to emerge as an internal one that belongs to the muse herself in relation to her maker, conceptually and collectively along the gallery walls.

“Do women have to be naked to get into the Met Museum?” The Guerilla Girls, an activist female artist collective, posed this question on the side of NYC busses in 1989. An updated version of this piece was displayed at the Venice Biennale in 2005. This later version includes recent statistics: “Less than 3% of the artists in the Modern Art sections are women, but 83% of the nudes are female." On display, historically and still, even in more modern times, the female figure is often viewed as a model, a muse, an object, or painting. She is rarely collected as an artist.

However, this is not to insinuate that there is a lack of women artists in the world—quite the contrary, especially in the realms of photography and performance. Jenny Holzer, most famous for her public contemporary usage of text as art, states, “It’s women who’ve been doing the most challenging art in the last decade. Psychologically seen, their work is much more extreme than men’s.”

Some of the most familiar female art star names are often associated with photography—Cindy Sherman, Diane Arbus, Dorothea Lange, Annie Lebowitz, and Nan Goldin, to name a few. Photography, in particular, seems to be the most interesting avenue for female artists to dominate in the sense that they can investigate their own bodies and their own ways of looking at the bodies of others through such a modern medium, which often, in popular tabloid magazine culture, is known to entrap or exploit its subjects, specifically women, in the name of documentary or reality. In other words, women armed with a camera can be makers of their own images, or dialogue with these images from the past, as is the case with Buranakorn.

In Regarding The Pain of Others, Susan Sontag asserts, “Photographs objectify: they turn an event or a person into something that can be possessed. And photographs are a species of alchemy, for all that they are prized as a transparent account of reality.” Although this quote is in response to war photography and documentary work, in reference to conceptual photography a similar objectification, ownership, or personal agenda is possible as well. The camera, as a device, captures its subjects with one quick click, transforming multidimensional people into frozen images on paper that can be labeled, owned, sold, and bought.

Buranakorn’s “Veil” series seems conscious of this. She uses this “photographic possession” that Sontag addresses to comment on previous pieces built from the hands of her male predecessors. She does not rely on her model to inspire; instead, she collaborates with her model to explore the complexities of any woman and her maker—domestically, in the art world, and beyond.

|

|

about

writer

visual artist

publications & exhibitions

art blog

shop

links

contact

|

|